- Home

- Maria José Silveira

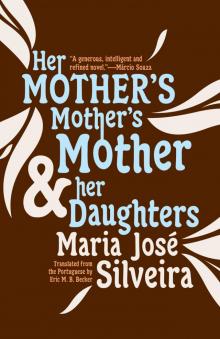

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters Page 6

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters Read online

Page 6

Thanks to the old woman and the protection of Manu, Maria Cafuza survived. When she entered the camp, the young girl had already erased from her mind everything she had seen up until then, even how to speak. The only thing left in her heart was the crushing, oppressive, convulsive impulse to hate João Tibiritê. From that moment on, her only purpose in life was to be consumed by this hate.

She grew up in the midst of that posse, without speaking and as though she understood nothing, like a wild animal. She accompanied them on their journeys, witnessed their battles, all the while turning over in her head the only thought she ever had—her obsession, her fuel, her water, and means of breathing—to kill João. Crouching down, sneakily trailing behind and hiding amid leaves and branches, Maria Cafuza observed each and every move her private demon made.

What’s curious is that João Tibiritê, experienced and observant as he was, never noticed Maria’s stare as it fixed on him; he never suspected that the hand that held his destiny was but a few steps away. It never occurred to him that the mute child he had taken with him on a whim, whom he had raised among his posse, could one day represent some sort of threat. He had practically forgotten about her, the withdrawn creature who lived concealed in the forest bushes, more beast than girl.

And so he was completely surprised when, after a night spent drinking in celebration of the capture of an entire Carijó tribe, Maria, all of fourteen, stealthy as a rattlesnake, slipped into his tent and prodded him with the tip of her dagger until he opened his eyes to see his approaching death and assassin. Then she plunged the dagger straight into his Adam’s apple, then again into his heart, and one last time through his liver, exhibiting the ability and anatomical knowledge of someone who had trained for years without rest for no other purpose but this.

João Tibiritê’s eyes flashed and he flailed about, but he was unable to cry out in horror and fear.

Manu was the only one who had seen Maria enter João’s tent, had seen her leave, but he didn’t interfere.

The following day, he assumed João’s place at the head of the posse.

Just as Maria had obsessively watched João’s every move, Manu Taiaôba watched Maria. The older the girl grew, the more bewitched Manu became.

Something interesting was happening there: the young slave hunter couldn’t make out why he had begun to dream about Maria instead of battles, as he’d done before. The young man, brought up in the harsh reality of the wilderness, the rush of adrenaline in the midst of war, and in the sole company of other brutes like himself, knew nothing about feminine beauty. There was no beauty at all in that universe of crude men who wouldn’t recognize a beautiful woman if they saw one. A person can only notice and understand what he has been taught to notice and understand. If he lacks the fundamental knowledge, some basic instrument to tell him what is and isn’t beautiful, how can he take notice?

This was exactly what happened in the case of Maria’s splendorous beauty: there was no one in the posse capable of taking notice. Only the old woman and Manu, without realizing exactly why, would spend hours on end staring at the young woman, and each time they looked, they felt something inexplicable and better inside themselves. And so it was the girl, rather than combat, who began to inhabit Manu’s dreams.

Manu asked the old witch to find him an herb to calm his mind, which was on fire, consumed with nothing but thoughts of Maria.

Each time Manu tried to draw closer, Maria would drive him away as she drove away the others. No one would ever touch her. All attempts to rape her—and there were many for the simple fact that Maria was a woman in such an environment—were thwarted by a vigilant Manu, who little by little made sure everyone in his posse understood that they were to leave Maria in peace, or they’d have to deal with him.

After the death of João Tibiritê, Maria felt something like disappointment that he could not come back to life so that, now that she had learned how, she could kill him over and over, until she, too, died, together with the hate she carried inside her.

Nonetheless, in some way something changed inside her—not by much, but enough that one night under a full moon, at the edge of a river, she let Manu approach her. He drew closer with such desire and such fear that it was nothing short of a miracle that anything happened there at all. But it did. Maria howled like a wild animal, but stopped when she finally understood that she wasn’t howling out of hate or terror, but for some other reason she couldn’t quite make out, but which she knew was not bad.

Her life, despite everything, did not change. Her uncontrollable hate for João Tibiritê, even after his death, left no room for any other emotion to occupy her mind and heart. She continued to lead her life in the same feral manner as before, at the side of the old Indian woman, trailing the posse wherever it went. On nights with a full moon—and only on such nights—she would go to the edge of some river and allow Manu to touch her.

Manu’s devotion to her was almost religious. He always set up his tent next to that of the old woman and the young girl, and did everything in his power to ensure they wanted for nothing.

The leadership of the tactical, adventure-seeking Paulista took little time to assert itself, and soon his reputation for success replaced even that of João Tibiritê, as did his aversion to unnecessary violence. Manu Taiaôba was no delicate flower, but he had no sympathy for violence for the sake of violence: he was of the opinion that honorable death in combat was the safest way to resolve matters and that, while the capture of savages was a necessity, he could not say the same for violent forms of punishment, which only served to delay their forward progress.

In the ten years that passed, his posse marched many times from the backlands of southern Brazil to the sugar-producing region in Pernambuco, in the north. Maria became pregnant twice, and twice, with the help of the old woman, she aborted. She was unable to tolerate even the thought of putting a child into this world. Never that.

That was when a plan began to take shape in Manu Taiaôba’s mind: to take Maria to the sugar plantation where she’d been born. Would she remember the time there when she could still speak? Would she recall memories of her parents that would rid her of the hate consuming her? His devotion to Maria caused his thoughts to wander in the hopes of finding something, anything, that would make life less of a burden to her.

They did, in the end, return to the old plantation. The Portuguese farmer who had hired João Tibiritê had already died, as had his wife. One of his sons had since taken over the mill, which continued to be a wildly prosperous enterprise. Under the pretext of talking over the idea of buying some land in the area, Manu requested permission to camp with his posse near the plantation.

They stayed for a while and Maria walked the land without any sign of recognition. She had merely become more given to contemplation: she would sit down somewhere and stay there for hours, looking out toward some unrecognizable point beyond the horizon.

Until one cold and cloudy morning, she got up and she set off like a zombie toward the margin of the nearby creek; she began to walk faster and faster, as though following a clear path she could see in her mind.

Manu followed her.

Maria walked a good distance before stopping beneath a leafy jatoba tree, where she crouched down and began to dig furiously until she lifted out a small package bundled in an old and dirty handkerchief.

Shaking, she untied the tiny bundle of Filipa’s treasures.

And then, her body no longer had the strength to hold back all the devastating, pent-up pain that she had carried all those years. As she fell to ground in convulsions, a terrified Manu felt he had committed an irreparable mistake.

But just look how life is full of surprises.

Maria Cafuza, this time without suspecting a thing, was pregnant. She’d barely gained any weight, her belly had hardly grown at all, and though she had a slight suspicion, she still lacked the certainty to take the necessary precautions. Perhaps her own arrival at the plantation of her childhood had lifted her

thoughts to somewhere other than her body, and nature continued on its course without her or the old woman noticing a thing. But that day, there beneath the jatoba tree, everything happened at once: Maria writhed with painful contractions, without realizing that, as she died, taking that incurable pain with her, she gave birth to a daughter.

Had she known better, she would have killed her.

MARIA TAIAÔBA

(1605-1671)

&

BELMIRA

(1631-1658)

The city of Olinda—seated atop a lush hill flooded with green, with a view to the forest and to the azure sea—was, for many people, perhaps the most beautiful city in the entire country. And one of the largest, with its houses of stone and quicklime, brick and tile, its mother church with its three naves and many chapels arranged in such a way that the faithful could take few steps within its confines before feeling summoned to contemplate their souls. The streets were bustling with herds of animals passing by, with slaves—either savages or from Guinea—coming and going to fulfill their duties, the stores with their open doors and shelves full of goods, the streets paved in bright stone.

Manu Taiaôba looked around at it all and became dizzy. He had been to many villages and settlements and to the cities of Piratininga and Bahia, but Olinda left him with a nearly uncontrollable anxiety to run back into the forest. All the people and animals swarming through the streets, the harshness of the ground where his bare feet never managed to firmly grasp the cobblestones, the loud hum of conversations, oxcarts, animals, the nauseating mixture of the scent of sweat and food—it was all too much and too disturbing.

But he was there to negotiate the purchase of his land and would not leave until he had succeeded.

On the afternoon he had buried Maria Cafuza, the slave hunter swore to himself that he would never let his daughter grow up living the slave-hunting lifestyle that had done so much harm to her mother. He decided to settle down and buy some land in the region between Recife and Olinda, an estate where he had seen an enormous sugarcane plantation, a true beauty, where each sugarcane plant was uniform in size, packed in close, so nearly identical that they appeared to form a sea of green leaves as far as the eye could see. Manu knew nothing of planting sugarcane, but he was certain he could learn. Whoever among the posse wished to stay with him was welcome; whoever did not could strike out on his own, no hard feelings. The only thing Manu wanted now was to buy the plantation. He had seen a house of quicklime and stone next to the sugarcane fields: that is where he would take his daughter and the old witch-woman who had watched over Maria and who now watched over the child.

“Give her the same name as her mother,” he said as he handed the premature child, still covered in fluids, to the old woman. “And find a place for this, it’s hers.” He handed her Filipa’s treasure, the filthy cloth bundle full of tiny objects whose importance could only be appraised by someone like the old woman.

Yes, Manu knew the old woman could take care of everything. The old woman, whose name he never learned, or if she ever had one, had gone by simply “old woman” ever since she began following João Tibiritê and his posse, and though at that time she wasn’t even old—she couldn’t have been much more than twenty—she already had an old woman’s way about her that seemed to have been hers since birth: the face of an old woman, the mannerisms of an old woman, the wisdom of an old woman. Daughter to an Indian man and a black woman, or perhaps a child of the forest—this, too, no one could say for certain—she was versed in incantations, she knew how to recognize medicinal plants, she could speak with the animals. If João Tibiritê allowed her to always remain close to his posse without bothering her, it was because the old woman had saved João’s life the time he had been bitten by a venomous snake—it had been at the exact moment she had first stepped forth from the forest, saying she would cure him. And she did. Rumor had it she had ordered the snake to bite João to later gain his favor, but those who claimed this could never prove it, and since the old woman was a good person, it’s likely simply coincidence that she had been passing through at that moment and had decided to stay.

For his part, Manu Taiaôba, in his old age, mulling over all that had happened in his life, was convinced that the old woman had joined up with the posse because she was predestined to care for the two Marias. He recalled that João Tibiritê had only decided to let her stay after Manu made him see that a medicine woman was a good thing to have around in a life spent in the forest and in battle, as had proved to be the case with João himself and the snake bite. Manu also recalled that he wasn’t sure why he had said this to João, since he had no reason or authority to meddle in the decisions of the leader; he was merely just one of the gang at the time, João hadn’t yet named him his right-hand man.

But it’s just such inexplicable things that make life what it is, and if the old woman hadn’t joined up with the posse then and there, neither the second nor the first Maria would have survived. If the most the old woman could manage with Maria Cafuza was to help her survive, in the case of the second Maria she was able to do much more. The two of them were inseparable. They were much more than mother and daughter could be, as neither had any obligation to the other; it was nothing more than pure necessity and a fondness for each other’s company and doing nearly everything together.

The old woman was Maria’s shadow and a bit of her soul: the old woman told Maria stories of the lives of Maria Cafuza and Filipa, taught her the secrets of medicinal herbs, explaining the cause of each shade of green to be found in the forest, she taught her about animals and their purposes, she showed the girl the course of the river-spirit and its waters, and, most importantly, she had taught her from a young age to peer deep inside herself to discover the source of her unique strength and power.

Maria Taiaôba had neither her mother’s beauty nor her wild character, but she had inherited her father’s strategic mind and his innate and even unconscious tendency to appreciate and seek out the unknown.

When she was a young girl, she would go with the old woman to Olinda and they would sit on a bench in the middle of the square and watch the people walk by. Maria would visit the churches, admiring the saints and the smell of burning incense; she walked along the sidewalks and admired the interiors of the homes through the open doors and windows; she would walk into stores and gaze at the shelves; she looked down from the top of the hillside onto the port, at the ships loading and unloading, the glimmer of the Capibaribe and Beberibe rivers, the azure spell of the Pernambuco sea. Maria loved all of that; her heart swelled with the beauty of the landscape and the old woman observed without any surprise that she was the exact opposite of the dark, troubled soul her mother had been.

Still a girl, Maria began to notice that something important was missing in her life: the ability to read. Sure of herself, she knew she could do anything and, after asking around and around, she found the house of a teacher where only young boys went to learn Portuguese, Latin, and arithmetic, but whose wife did teach young girls to read, write, count, and sew.

Twice a week, Maria and the old woman, departing the plantation on horseback, climbed the hillside to Olinda. Maria would go to her classes and the old woman would sit on a bench near the mother church, where she was approached by the women of Olinda eagerly seeking remedies for abscesses, nocturnal fevers, all manner of pain, and love potions. The old woman patiently attended to all of them, for this was her calling and she practiced it with great generosity.

The girl’s father, Manu Taiaôba, watched his daughter grow up in a way unfamiliar to him, but which intuition told him was good and well. The plantation he bought sat on moist soil, and the land was good and fertile. Relying on native slaves, he soon began producing great amounts of sugarcane, which he sent to be ground up at Engenho Santo Antônio next to his plantation. As a creature of the jungle and an adventurer, however, Manu had begun to grow restless; at night he would hang his hammock far from the house, and during the day he practically never set f

oot there, not even on the veranda. His daughter would go fetch him in the fields or wherever he was and bring him food. There the two of them would eat together, Manu crouching while Maria sat on some fallen tree trunk telling him what she had seen in the city as he barely said a word—not for a lack of interest, but because he wasn’t sure how to respond and because of the sound of his daughter’s voice, that limpid tone that most certainly would have echoed Maria Cafuza’s if the woman had ever spoken. It was as though only the sound of the girl’s voice could bring him more peace than the placid murmur of the serene waters of a tiny mountaintop stream, and that was enough.

And so the day arrived when, watching as the time passed quickly and seeing how well off his daughter was at the old woman’s side, sensing that the two of them no longer needed him, Manu felt free to seek out some other life more in accord with his temperament. He could raise cattle, animals that were becoming increasingly necessary for the colony’s food supply, for the production of the sugar factories, and for transportation, which at the time was done exclusively via oxcart. He longed to roam the land with his cattle, opening new routes through the dark heart of the dense forest, and to return to the rough life he had known growing up, sleeping beneath the open sky, hunting for food, battling Indians.

He bought a small house in Olinda, where he left the old woman to take care of his daughter, along with some slaves and a few reliable men; he named another of his men foreman of the sugarcane plantation, and with part of his old posse he set off on a cattle drive toward the deserted backlands, toward the Rio São Francisco.

Later, he would always visit his daughter to listen to the sound of her voice, this sound that followed him day and night through the backlands and left him with something like a soothing warmth inside his chest. He would arrive in Olinda, negotiate for the cattle, and check in on the plantation, but he never stayed in the city for more than a day at a time.

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters