- Home

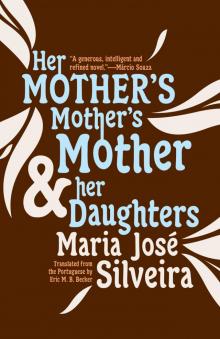

- Maria José Silveira

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters Read online

Copyright © Maria José Silveira, 2002

Translation copyright © Eric M. B. Becker, 2017

Published by special arrangement with Villas-Boas & Moss Literary Agency & Consultancy and its duly appointed Co-Agent 2 Seas Literary Agency

Originally published in Brazil as A mãe da mãe da sua mãe e suas filhas

First edition, 2017

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Silveira, Maria José, author. | Becker, Eric M. B., translator.

Title: Her mother’s mother’s mother and her daughters / Maria José Silveira; translated from the Portuguese by Eric M. B. Becker.

Other titles: Mãe da mãe de sua mãe e suas filhas. English

Description: First edition. | Rochester, NY: Open Letter, 2017. | First published as A mãe da mãe de sua mãe e suas filhas.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036349 (print) | LCCN 2017048876 (ebook) | ISBN 9781940953724 (Ebook - EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Mothers and daughters—Fiction. | Women—Brazil—Fiction. | Families—Brazil—Fiction. | Brazil—Social life and customs—Fiction. | Domestic fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Literary. | FICTION / Contemporary Women. | HISTORY / Latin America / General. | FICTION / Historical.

Classification: LCC PQ9698.429.I48 (ebook) | LCC PQ9698.429.I48 M3413 2017 (print) | DDC 869.3/5—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036349

This project is supported in part by an award from the National Endowment for the Arts

Design by N. J. Furl

Open Letter is the University of Rochester’s nonprofit, literary translation press:

Dewey Hall 1-219, Box 278968, Rochester, NY 14627

www.openletterbooks.org

For my mother Galiana and my Aunt Sina,

Gali, José Gabriel, and Laura. For Felipe.

Just as you see me now, I carry centuries within me: numbers, names, a place among worlds and the force of the everlasting.

—Cecília Meireles, “Trânsito”

CONTENTS

A Shortlived Romance

Inaiá (1500-1514)

Tebereté (1514-1548)

Desolate Wilderness

Sahy (1531-1569)

Filipa (1552-1584)

Maria Cafuza (1579-1605)

Maria Taiaôba (1605-1671) and Belmira (1631-1658)

Guilhermina (1648-1693)

Improbable Splendor

Ana de Pádua (1683-1730)

Clara Joaquina (1711-1740)

Jacira Antônia (1737-1812) and Maria Bárbara (1773-1790)

Damiana (1789-1822)

Vicious Modernity

Açucena Brasília/Antônia Carlota (1816-1906)

Diana América (1846-1883)

Diva Felícia (1876-1925)

Ana Eulália (1906-1930)

A Promising Sign

Rosa Alfonsina (1926- )

Lígia (1945-1971)

Maria Flor (1968- )

Inaiá (1500-1514) + Fernão; in the new region of Porto Seguro/Bahia, near Monte Pascoal.

Tebereté (1514-1548) + Jean Maurice; in the region of the Cabo Frio/Rio de Janeiro trade post.

Sahy (1531-1569) + Vicente Arcón; on a farm near the boast of Bahia.

Filipa (1552-1584) + Mb’ta; on a farm in Bahia and a sugar mill in Recife.

Maria Cafuza (1529-1605) + Manu Taiaôba; between São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Bahia, and Pernambuco.

Maria Taiaôba (1605-1671) + Duarte Antônio de Oliveira; in Olinda and Salvador.

Belmira (1631-1658) + Wilhelm Wilegraf; in Olinda and Salvador.

Guilhermina (1648-1693) + Bento Vasco; in Olinda, Salvador, and the border between Espírito Santo and Minas Gerais.

Ana de Pádua (1683-1730) + José Garcia e Silva; in Sabará/Minas Gerais.

Clara Joaquina (1711-1740) + Diogo Ambrósio; in Sabará and on a farm in central Rio de Janeiro.

Jacira Antônia (1733-1812) + Captain Dagoberto da Mata; on a farm in central Goiás.

Maria Bárbara (1713-1290) + Jacinto; on a farm in central Goiás.

Damiana (1789-1822) + Inácio Belchior; on a farm in central Goiás.

Açucena Brasília/Antônia Carlota (1816-1906) + Caio Pessanha; in Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, and São Paulo.

Diana América (1846-1883) + Hans G; in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Diva Felícia (1826-1925) + Floriano Botelho; in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

Ana Eulália (1906-1930) + Umberto Rancieri; in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

Rosa Alfonsina (1926-. . .) + Túlio Faiad; in central Minas Gerais and Brasília.

Lígia (1945-1971) + Francisco da Mata; in Brasília and Rio de Janeiro.

Maria Flor (1968-. . .) + Joaquim Machado; in Brasília and Rio de Janeiro.

All right.

If that’s how you want it, I’ll tell you all the story of the women of the family. But let’s take our time.

It’s a sensitive subject, the family is a difficult one, and not everything in this story is wine and roses. There was, of course, love and happiness, battles and victories, great feats—after all, the women in this story helped to build this country, nearly from the ground up. But there were also madwomen, murderers, and a fair share of sorrows and tragedies. Great disappointments. A good many of them.

Remember, too, that whatever I tell you, it was you who asked me, this time, to recount the lives of these women. If at some point you think I’m passing over the men too quickly, don’t come to me later accusing me of feminist bias. I’ll tell you all right now that the lives of the men of the family are every bit as interesting as those of the women, and if I don’t wade further into their exploits, it’s only out of respect for your wishes.

And since it is almost time, let’s begin our story where it began.

With Inaiá, the little Tupiniquim girl, the origin of it all.

A Shortlived Romance

INAIÁ

(1500-1514)

In the crimson twilight of dusk cloaking the sea, when after forty-two days the sailors of the Portuguese armada glimpsed the first long, flowing seaweeds stretching across the dark green ocean, a clear indication they were nearing land, Inaiá’s mother, standing on the packed earth of her village’s ritual grounds, cast her eyes toward the first stars and knew immediately: It was time.

When the darkness blanketed everything and the sailors on the ship had gone to their bunks with their hearts in a stir, tipsy from the wine consumed during the anticipatory celebration of their arrival in an unknown land, Inaiá’s mother turned over on her side in her cotton hammock and felt the initial pang announcing the contractions to come.

Early the next morning, as the sight of seagulls with their black feathers and white heads transformed the sailors’ anticipation into a swell of euphoria and set the bells of the armada chiming, back at her tribe’s village, Inaiá’s mother stretched to her feet and resumed the previous day’s chores beneath the turquoise sky.

During vespers on that twenty-first of April, the jubilant sailors, leaning over one another on the decks of the armada’s twelve vessels, caught glimpse of a tall, round mountain at the exact moment Inaiá’s mother stole away to the quiet spot in the forest that she’d chosen for that day, on the banks of a tiny river with crystal waters whose depths reflected the emerald green of the surrounding trees.

When the sky once again began to grow dark and each ship had dropped anchor, the sailors fell to their knees in gratitude at the sight of the thick forest just beyond a thin strip of white sand; the birds along the riverbank leapt skyward once again, startled at the s

ound of Inaiá’s first cries.

Inaiá’s father, a Tupiniquim warrior, cut the umbilical cord with his teeth. Privately, his heart leapt with joy because this time the child was a girl; it would not be necessary to remain abstinent in his thatch hut for days on end, protecting her from evil spirits. He would be able to join the group of warriors in their vigil on the beach, watching in wonder as the marine giants approached steadily across the sea.

Before the first rays of sunlight tinged the morning that followed, he was at the water’s edge with the rest of the group, eight Tupiniquim warriors armed with bows and arrows. From there they observed the portentous approach of the twelve ships and caravels. Their eyes followed the tiny sloop nearing the beach, carrying creatures they’d never before seen. They wondered excitedly: what were those things?

The warriors on the beach numbered more than twenty—naked, strong men adorned with body paint and green, yellow, and red feathers, tensely clutching their weapons. They saw the signs exchanged between those strange creatures and heard their cries in a foreign, incomprehensible tongue that the roaring sea carried far away. The cresting waves kept the sloop from reaching the beach, but the warriors remained there the entire night, keeping watch while huddled around a tiny bonfire.

The next morning, nearly the entire tribe was on the sand to see the caraíbas, the prophets come from the East, the land of the sun. What they saw instead was the armada pull away to the north. At this, everyone, these warriors and a good number of the tribespeople who were now much too curious to return to their village, immediately decided to follow the ships by land or in tiny boats.

Little by little, they arrived to the place where the armada dropped anchor for a second time, a few days’ walk from the village.

Even Inaiá’s mother—who joined the expedition three days later—her child slung across her back, managed to arrive in time to see a cross erected on that first day of May. Two enormous pieces of intersecting wood raised skyward to the sound of music, chanting, and processions by those creatures with their strange white skin covered in fur, like animals. They were armed to the teeth, these strange men who, by fate’s design, were welcomed as friends and brothers.

It might be said, then, that even if she didn’t actually see a thing, Inaiá took part in the event that would forever change her life and that of her people.

Her tribe was enjoying a period of relative peace. The men hunted and fished. The women planted cassava, ground it into flour, and made cauim wine, wove ornate baskets and made pottery. They’d arrived at that fertile tract during their pilgrimage in search of the Land without Evil, and though there were occasional wars with other tribes, these were part of the natural order of things and did not otherwise disturb those days Inaiá and her sisters spent without serious worries. They bathed in the river, played with the forest animals at the edge of the village: they could identify each type of snake, sneak up on birds and marmosets, anteaters and sloths. They were capable of recognizing each plant and tree, and where it was safe to cross the river. They would help their mothers peel the cassava and they learned to make flour and cassava pancakes. When night fell, the girls would huddle next to the adults around the bonfire to listen to their stories and their laughter, to learn how to dance, make music, and play games.

Inaiá grew up with the belief that, above all else, people were supposed to enjoy life, and that we were born to find pleasure in each day. Melancholy and sorrow were sentiments that provoked great displeasure among the natives. They believed the gods were kind, and the idea of a life after death entailed a garden full of flowers where they would sing, dance, and leap around at their ancestors’ side.

Inaiá also grew up listening to stories about the caraíbas who had arrived with the sunrise on the day she was born.

The events witnessed during those ten days in April and May were recounted again and again by the adults in the tribe, thousands of times, each individual adding a new point of view, teasing out another detail, as if the act of repeating these stories were a way to help them make sense of those stunning changes to their world by making them a part of their lives instead of a disruptive chaos. They passed the cascabels, mirrors, and beads from hand to hand—gifts from the white man. They placed the sailors’ red caps on their heads and danced around, imitating the recently arrived visitors, their pirouettes, their way of walking and moving about.

A time or two, Inaiá caught sight of the caraíbas visiting her tribe or walking along the sands at the edge of the sea, next to the logs of Brazilwood trees that now filled the beaches awaiting the men’s enormous ships. The hairy men weren’t as imposing as she’d imagined when listening to the descriptions given by those who were present when they first arrived. In fact, in the flesh, those figures didn’t impress the young Tupiniquim girls in the least. They would laugh out loud at the men’s ragged clothing, which looked like a second skin hanging from bodies that were no longer all that white after months beneath the tropical sun, though they were still of a color Inaiá found unusual. She and the others found especially amusing the hairs that seemed to grow every which way and covered the men’s hands, bodies, entire faces. They would laugh once again before trailing the sailors, offering them whatever they found along the way and receiving in return kind or impatient smiles, a flurry of gestures and the endless repetition of the same words used to express nearly everything. On occasion, they saw some who were better dressed, wearing colorful second skins—these, indeed, pleasing to the eye—and a headdress not of feathers but of fur, and a strange sort of shell covering their feet.

The adults in the tribe now spent a good part of their time felling trees of a certain red wood, trees the color of burning embers, those magnificent trees whose dye would be used to make the most fashionable clothes in Europe. The right to don this majestic color, previously reserved for kings and Church prelates, had been extended to all, and the demand for the tree’s purple-colored dye had intensified. Those natives who possessed steel machetes, gifts from the caraíbas, were able to cut the trees with much greater speed, frenetically hacking away, proudly gathering rows of Brazilwood trunks in a few short hours. Had Inaiá lived a bit longer, she would have seen how, day after day, these trees with their metallic green leaves, yellow flowers, and red trunks—found everywhere in her childhood—slowly headed toward extinction.

What was Inaiá like, you ask?

Well. Inaiá was never especially beautiful. I realize you all would like it if this woman with whom it all began, this nearly mythological mother figure, were as perfect as in a fairytale. But she wasn’t. If I said she was, it would be bending the truth, although any judgment is relative, of course, both because the standards of beauty of an indigenous tribe at that time are not the same as ours today, and because beauty has never been an absolute truth. There will always be those who consider what the majority finds beautiful to be ugly, and those who find beauty in what the majority judges to be lacking in it. But it’s pure foolishness to try to idealize the very first woman in our family. There’s no reason for it. It’s enough to know that, in every way possible, the first inhabitants of our country attracted many a stare, as was noted by none other than the illustrious penman Sir Pêro Vaz de Caminha in the first document written about this new land. It appears he was unable to take his eyes off them, as he himself admits, and was incapable of concealing his fascination: “So young and so full of charm, with long hair black as night, and their privates so tiny, so slender, so free of hair that, after observing them at great length, we too felt no shame.”

We’ll never know for sure if all the women were so eye-catching—and if Caminha saw them from a distance or was able to examine them up close—but that shouldn’t cause you to think that Inaiá was a beauty among beauties, because she was nothing of the kind. She was plump and of average height, a bit asymmetrical in relation between her torso and her legs, the latter being skinnier than some might like, her buttocks were simply average, neither large nor small, neither f

irm nor flaccid, her bosom ample but fated to succumb to the law of gravity at an early age, and her black hair was long and straight like that of all the native women, neither more nor less silky than all the rest. She had a flat nose, average black eyes, the same red mouth as her sisters, and a birthmark—this last detail a characteristic all her own—a dark triangle near the base of the nape of her neck that tilted left near its peak. But beyond this, not even Inaiá’s personality was particularly exceptional. She performed daily chores eagerly and splashed about as she took baths in the river, and was as social and carefree as her sisters, as well-mannered and happy to be alive as they were.

After a time, she no longer trailed the groups of white men. She maintained a distance, along with her sisters, the whole of them laughing out loud. But their laughter was already different, something in their gazes had changed. That was when one of the men—a caraíba about her age by the name Fernão, with an extraordinarily white face nearly devoid of hair, with bright eyes that looked like little rocks made of crystal-clear seawater—cast his eyes on her, smiled, and began to repeat:

“Here, over here. Pretty girl, come here.”

Inaiá went. She was twelve years old.

A smile on her face (she had never been so close to a caraíba), the curious Inaiá inched forward. She reached out to touch him, touched him and laughed, she smelled him, smelled him and laughed, his flesh was so white beneath that second skin and she laughed, his hair the color of falling leaves, she touched him and smelled him and laughed: Those eyes, yes, I want to see up close these crystals the color of the sea as it nears the sand, the sea without waves, the sea just after the day has begun.

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters

Her Mother's Mother's Mother and Her Daughters